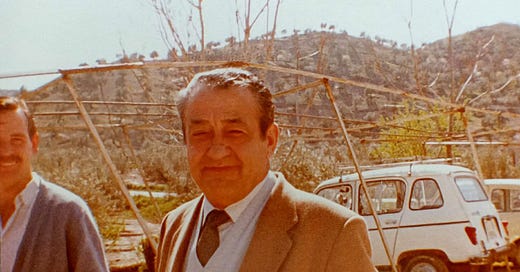

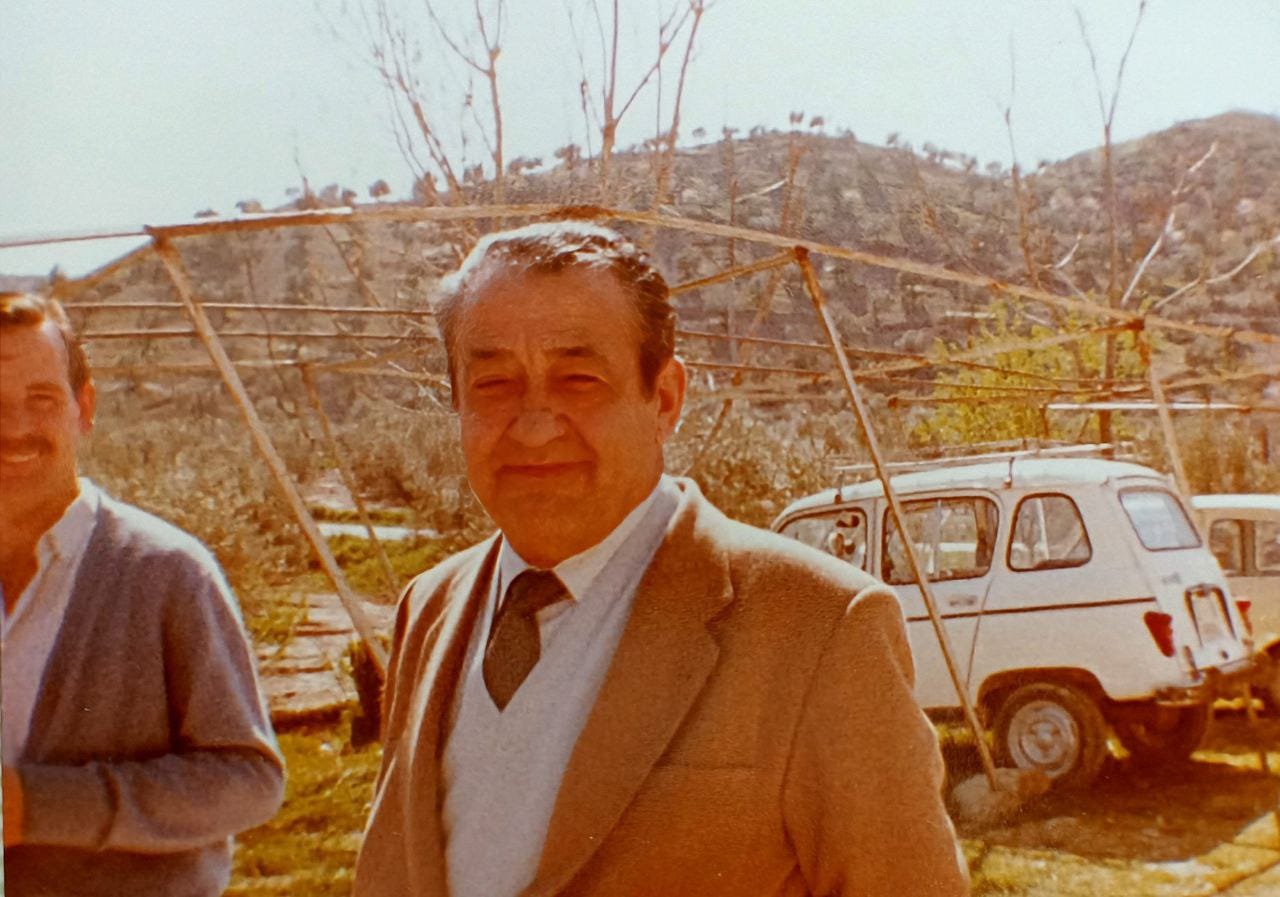

When I was a boy, Grandpa dreamed of me becoming a torero—a matador, a bullfighter. He was a man of his time, traditional, hardened by the struggles that shaped his generation in Spain. But unlike so many others, he kind of thrived. Success hung on him as naturally as the cigarette on the edge of his lips. He was tall and strong, with bronzed skin and slicked-back hair. He spoke very little, always watchful, the smoke curling from his lips as if it were a part of him. He was a businessman, fair but tough, though to me, there was something of a gangster in his looks.

Now, picture me beside him: a chubby six-year-old bookworm and no more fight in him than it took to claim first or second place in the classroom. He, a big Grandpa Gangster. Me, a child who dreamed of inventions, computers, and robots. He, wanting me to fight a 500 kg bull…

I remember the day he took me to my first corrida1, the heat of the sun, the roar of the crowd, the stickiness of the flies, and the terrible sight of the bull bleeding out onto the sand. That was the first time I saw death, the blood, the spectacle—and it was the last time I would ever watch it. Even as a child, I felt a revulsion for the cruelty of it. So that evening, I sketched the blueprint for a robotic bull, a mecha, that could be defeated by a matador wielding not a sword but some sort of lightsaber. Yet another child’s fantasy, born in a mind that preferred the mechanical to the bloodied.

Years passed. I moved to the city, struggled to find my place in a new school. Gone was the comfort of being the smartest kid in the room. Now I was just trying to survive. And it stung. It was a lonely time. I visited my grandparents one weekend, and when I saw my Grandpa again, he was changed. The man who once seemed invincible was now tethered to a noisy oxygen machine. His hair and skin had paled, the cigarette replaced by a toothpick that danced on his lips with the same careless grace. The machine wheezed beside him, but he still carried that aura of the old gangster. He looked even more badass to me, like a cyborg or something like that. He paid a high price for years of smoking, one that had stolen his breath.

He asked me how I was faring at the new school. His question landed squarely on a wound I was still licking. “Not well, Grandpa. I’m failing. Even music and sports.” For the first time in a long while, he laughed, a rare sound that felt almost cruel. My cheeks burned as I looked down, embarrassed. “A torero in his village,” he said, “but out there? Not even a banderillero2.” He knew, as I did, what it felt like to be knocked down a rung. I sat there, chewing over the humiliation. His toothpick spun as he thought. But in his silence, I felt my failure even more deeply. Then, after a moment, he glanced at me from the bottom of his dark circles and asked, “Do you still like building and fixing things?” I nodded. Of course I did. I had a knack for taking things apart, less so for putting them back together. “Then you should be an Engineer,” he said, as if it were the simplest thing in the world. I had never heard that word before. “What’s an Engineer?” I asked. “Someone smart, who invents and fixes complicated things,” he replied. “But you’ll have to work harder if you want to be one.”

That moment stayed with me. The old expectation that I would one day face down bulls was gone, replaced with something far closer to who I was. His words gave me something I needed—a direction, a recognition of my own inclinations. He was giving me permission to be myself, to follow my own path. That quiet push from him, so simple, was enough to reignite my love for learning.

He died a few months later. And it was, perhaps, the last advice he ever gave me. Do you want to do something you love? Then work harder.

I did better, but never became the top student again. Mediocrity dogged me for years, and when I eventually pursued Engineering, there were countless moments when I wanted to quit. Many of my peers did. But I remembered my Grandpa, the toothpick rolling between his lips, the knowing laugh, the hardness of his gaze. I pressed on, worked harder.

In time, I discovered that engineering was a worthy path, but for most, it confined them to a narrow problem space, a specific set of tools. I wanted more than that. I wanted to have the reach and freedom to think ahead, to build things that mattered and changed lives. So I became a Product Manager—a role where I could think like an engineer but act like a businessman, free to create with vision and impact. It took me years to connect these dots back to Grandpa. Even though he once dreamed I’d become a torero, he had, in a way, set me on the path to becoming something better suited to who I was.

Why am I telling you this? There’s no Stoic lesson here today, no moral wrapped up in tidy wisdom. I suppose I just needed to remember him, to remind myself of why I do what I do. Some stories of our childhood—they shape us, and sometimes they guide us back when we lose our North Star. When the days feel long and the work feels empty, it helps to think back. To remember why we are here in the first place.

And in writing this, I remembered: that mecha bull is still on my backlog.

Bullfight.

A second-class bullfighter, assisting the matador by placing barbed sticks (banderillas) in the bull to tire it out before the main fight.