Today’s newsletter is brought to you by the Cynical Product Manager™. You know, the one who doom-scrolls on LinkedIn, wondering why half of the product world is drunk on their own magic potions.

Bear with me.

If you’re a PM, Product Owner, or juggling both, you’ve likely felt like a colossal failure. Why? Because every expert seems to have an opinion on how to do your job—and you’re expected to swallow an endless stream of frameworks, certifications, and 'best practices' without choking

Because…

Product management is fertile ground for dogma.

Especially in software. Let’s unpack why:

Vaguely defined by context. Everyone knows what a Sales Manager does. A PM? Depends on the context.

Different industries, different beasts. The PM at a legacy bank might be herding cats with Gantt charts, while the PM at a sexy startup is throwing darts at a Notion board. And at Telegram, the only PM is Pável Dúrov, the CEO.

It’s a relatively young job. We’re still figuring it out, but everyone pretends they’ve nailed it.

Greenfield = $$$ for consultants. Consultants and product schools, are cashing in because there’s always someone willing to pay for "the truth." Spoiler: In Product Management there’s no absolute TRUTH.

Oh, and there are way too many books. (I own most classic. I’m ashamed.) Some of these books are borderline cult manifestos. I’d call them out by name, but I’m not trying to start a flame war. Let’s just say Marty Cagan gets a pass for occasionally breaking ranks, and slapping other arrogant wannabes. But even he’s also making a life out of “best practices.”

I’m not charging you for this sermon, so I’m under no obligation to sugarcoat anything.

Best Practices… of what?

Let’s talk about the industry’s favorite phrase: “Best practices.” Ok, but best in relation to what? What are the alternatives? In what context? Are we seriously comparing everything to Silicon Valley? Newsflash: Not everyone is building the next Snapchat for dogs.

You think the same practices work for an internal developer platform and a consumer mobile app?

A “best practice” is just a fancy way of saying, “This worked for me once.” It’s not a law.

Classic examples:

“Use OKRs to align the entire org.” Sure, if your company is disciplined enough. But for messy, fast-moving orgs, OKRs incentivize shallow wins over meaningful progress. Sometimes a simple “What will move the needle this quarter?” works better.

“Always prioritize outcomes over outputs.” Sounds sexy, right? But some industries (hello, enterprise SaaS) require you to build outputs to sell. Without those, there are no outcomes to measure. Note: Just try not to become a sales-led Titanic.

“User research is mandatory before every feature.” It’s essential for complex problems. But for obvious fixes (e.g., "users want a dark mode"), just build the damn thing!

“A roadmap should be a vision document, not a to-do list.” Try selling that idea to a board who wants predictable delivery. Good luck.

“A perfect PM:Engineer ratio is 1:5” I’ve seen teams work beautifully with 1 PM for 20 engineers, and others flop with a 1:1 ratio. Even 1:0 — PMs without a dev team. It’s context, not calculus.

“Be data-driven.” Being data-driven is great—if the data actually exists and isn’t garbage. Sometimes you’re left with qualitative knowledge, anecdotal user feedback, and gut feeling.

Case studies, patterns, and common pitfalls are still insightful if you understand their context. But…

Best practices make sense in specific contexts—but they fall apart when used like gospel. A real PM is a pragmatist, not a preacher.

Jurassic Scrum

Years ago, I got my Scrum Product Owner certification. Like many naïve PMs, I thought I’d struck gold. Before Scrum, I managed a small but motivated dev team with no Scrum Master, no Agile Coach, no Engineering Manager. Just me, they, some common sense, and coffee. Things were fine.

Until I drank the Scrum potion.

Empower the team!

Accelerate agility!

All the shiny buzzwords seduced me, and I proposed to hire a Scrum Master to do Scrum by the book.

Bad idea.

Picture this: An old-school German company, where every corridor smelled faintly of waterfall and bureaucracy. They even had red carpets and Grandma’s furniture. Scrum wanted a paradise in the middle of Jurassic Park...

My shiny new Scrum Master lasted all of four sprints before fleeing down chased by a T-Rex, tears streaming, while I quietly died inside.

And then there was a blunt-as-hell frontend Dev. He slapped me with the cold truth: “Ángel, if we’re not gonna do real Scrum, why the f*** did you hire a Scrum Master?”

Fair point. I got seduced by a dogma and wasted months learning that Scrum isn’t a magic wand—it can be a liability in the wrong context.

The success of any framework often depends on thoughtful implementation rather than rigid adherence.1

The Proxy Product Owner controversy

“I learned to recognise the thorough and primitive duality of man; I saw that, of the two natures that contended in the field of my consciousness, even if I could rightly be said to be either, it was only because I was radically both.”

― Robert Louis Stevenson, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

There is consensus among the experts:

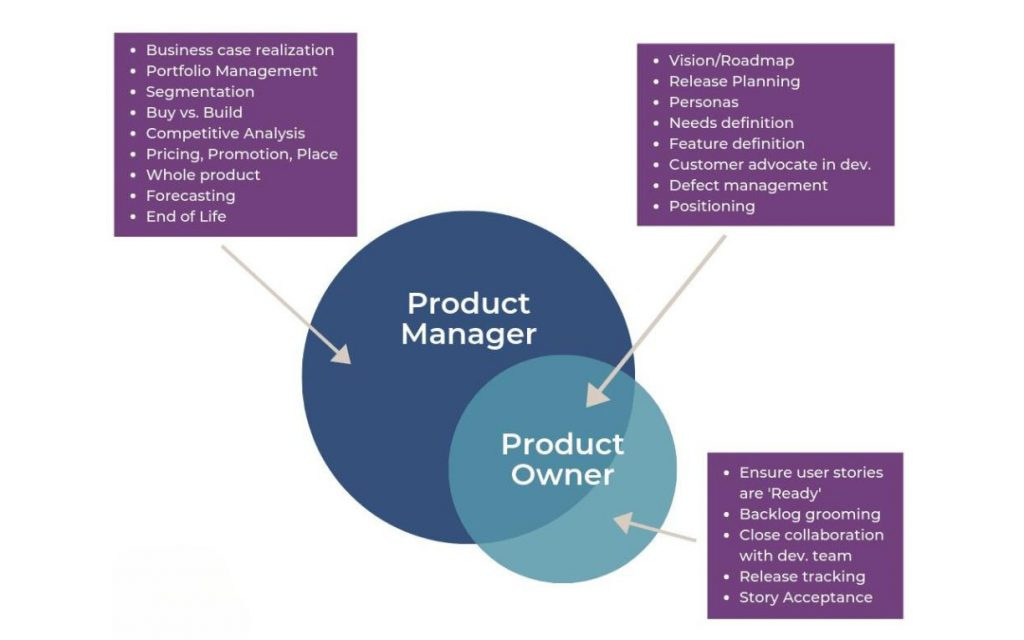

The PM is the job.

The Product Owner is a role, or a subset of responsibilities, specifically for dev teams.

Both must be played by the same person, like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Nice and clean, right? Very often, yes. And in principle, I fully agree.

While often symptomatic of poor structure, Proxy POs can serve as a practical stopgap in high-demand contexts or when scaling quickly. A Proxy Product Owner is someone who acts as the go-between for the PM and the dev team. Purists hate it, but it’s a band-aid that works when PMs are stretched too thin.

Is it ideal? No.

Does it work sometimes? Hell yes.

Here’s the reality:

Not every company has resources to split a product space into smaller product lines and hire dedicated PMs for each; or it isn’t the right time to build a more hierarchical product division (i.e. a dedicated Product Director or a Group Product Manager).

Not every PM has the bandwidth to juggle massive product spaces without letting some group of people suffer: sometimes it must be either the business stakeholders and the customers; sometimes, the dev teams.

So occasionaly, a PM has to rely on a proxy person or team to handle key PO activities, such as refining stories to be development-ready and tracking releases. How deep a PO must be involved, also depends on the maturity of the team and the company culture. That’s why sometimes you get this rara avis of Technical PO job descriptions, who are a sort of Tech Lead++ (who by the way thrive on Feature Factories). You may also see a Business Analyst working as a PO while a PM orchestrate the entire thing as “Business Owner”.

Does the Proxy PO introduce an ugly gap? For sure. But I’d take a managed gap over chaos and unfulfillment every day of the week.

The key is to ensure the Proxy POs are transitional, not permanent.

Engineers reporting to Product?

Ok, this is probably the hill I’ll die on.

Should engineers report to PMs? Most IT philosoraptors will tell you, “No f***ing way.”

But let me throw a wrench into that principle. In some contexts—small teams or PMs with engineering chops—it can function just fine.

Once seen, you cannot unseen it.

Sure, it’s unconventional, but it cut through noise and created accountability.

Because, you know what’s worse than engineers reporting to a PM?

An unnecessarily overcomplicated RACI matrix.

Unclear authority.

And org politics.

PMs proposing Technical Solutions

Ah, the golden rule: “PMs bring problems, engineers bring solutions.” Sure, that’s cute in theory, but in practice? There are exceptions.

Jeff Bezos famously dictated Amazon’s 1-Click Ordering feature, ignoring the usual discovery process. Engineers built it, and it changed e-commerce forever.

Sometimes, the PM knows the problem space better than anyone and also know the technology. Or maybe they’ve built something similar in the past. In these cases, it just works.

But you know what makes this okay? Low ego.

When people are not married to a solution or to to their roles, they have constructive discussions. Which also means you have to be prepare to hear “This idea sucks.” and be fine with that.

The secret? A PM proposing solutions works when:

The PM deeply understands the problem space AND the technology.

There’s trust and ego-free collaboration with the engineering team.

The solution is pitched as a hypothesis, not a mandate.

The rule isn’t “never propose solutions.” It’s “know when to shut up and listen, but don’t be afraid to step up when you’ve got a killer idea.”

Feature Factories are Evil

A Feature Factory is a team or company focused on delivering features driven by external input—think sales requests or stakeholder demands—rather than user-driven discovery.

If I had a euro for every time a product Guru trashed Feature Factories, I’d buy a yacht and name it “The Double Diamond.”

Here’s the thing: Not every PM must be a “strategic visionary.” Sometimes, you’re working in a feature team, and the business knows what needs building. These companies may or may have not accepted the long-term risk of stifling innovation. If you know what you signed for, that’s fine.

You can still do meaningful discovery, shape better requirements, and ensure smooth execution.

Being a PM in a Feature Factory isn’t a sin. It’s a job. And you can do it damn well.

Metrics Madness

Let’s talk about metrics. You’d think these holy numbers were handed down from Mount Agile on stone tablets. Here’s the dogma you’ll hear in every product team meeting:

"If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it." Sure, but some of the most meaningful product decisions come from intuition or long-term bets.

"North Star Metrics will solve everything." They’re great for aligning vision, but they’re not a magic wand. Ever seen a team hit the metric but break everything else? I did.

"Vanity metrics are evil." Vanity Metrics are numbers that look impressive but don’t reflect meaningful success. Good. But sometimes they’re an early indicator of momentum. You don’t ignore HTTP requests per minute just because retention is sexier.

Let me tell you something about metrics: they are garbage if they incentivize shortcuts or gaming the system. Looking at you, velocity!

And never forget Goodhart’s Law. Never!

Metrics offer a starting point for discipline and reflection — useful until they are unreliable. Don’t worship them.

Do It By the Book or Be the Author?

I know, I know. Many of these arguments are merely anecdotal and might make me sound like I have PTSD... Maybe!

But if you ask around, you will hear hundreds of similar war stories from other experienced PMs. How many anecdotes do we need to dismantle a cult? Honestly, I don’t know. I can only talk about what I’ve learnt.

Look:

After the Scrum fiasco, I made up my own agile process called “Strömban” — a mix of Nexus, Kanban, and some internal process constraints. It worked for that team, in that context, in that particular moment. I would never try to apply that framework again anywhere else. Did it follow a single book in particular? No. Did it help to deliver value? Yes.

Here’s the moral of the story: Product management is messy, context-dependent, and irreverently human. While I reject “dogma”, even gurus offer lessons worth listening to and adapting. Take what works, ditch the rest.

And most importantly, don’t feel like a failure because some LinkedIn post made you question your entire career. Those people are usually there to sell you their book or course.

The only thing that matters is this:

Are you delivering value for your users and customers?

Are you doing it in a viable way that works for your business?

If your team is shipping value, unlocking business opportunities, and your users are happy, you’re already ahead of most product folks. Everything else is BS.

So, go forth and ignore the gurus, including myself. And if you’re a guru reading this, for f* sake, stay humble!

Here I’m assuming a level of judgment and experience that not all PMs may yet possess. For less experienced teams, starting with structured frameworks can provide much-needed stability and direction.

Loved your article, Ángel! What works for a PM or organization is not a magic formula for everyone. Indeed, the best is to keep learning & listening, share experiences, and do your mixology. Stay humble and use your critical thinking and curiosity as your best tools! 😉